Caribbean paradise holds on to its Swedish past

While Sweden's Caribbean colonial ambitions ended long ago, a group on the island of Saint Barthélemy is working to preserve the former colony's Swedish heritage, contributor Carina Chela discovers.

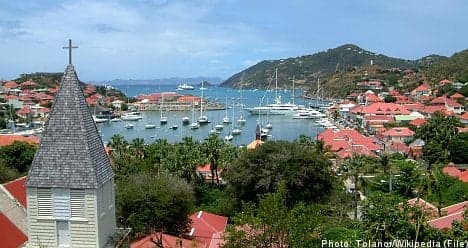

The crystal blue waters, warm temperatures, and jet-setting tourists of Saint Barthélemy bear little resemblance to Sweden's forested landscape and sometimes bone-chilling climate.

When first hearing mention of this small Caribbean island with a French sounding name, commonly known as St. Barts, one is hard pressed to make any connection to Sweden whatsoever.

Discovered in 1493 by Christopher Columbus, who named it after his younger brother, this roughly 20 square kilometre patch of land was taken over by the French in 1648.

But in 1784, Sweden's King Gustav III managed to negotiate the acquisition of what would end up being Sweden's longest-held colony in the western hemisphere by offering France's Louis XVI warehousing rights in Gothenburg.

On March 7th, 1758, St. Barts officially became a Swedish colony, ushering in almost a century of Swedish rule.

According to Leos Müller, professor of marine history at Stockholm University, Gustav III had ambitious colonial dreams for Sweden.

Apart from commercial interests, Gustav III also had a big political agenda for his growing empire, believing a colony in the Caribbean would "confirm Sweden’s status among the great European nations", Müller explains.

While Gustav III had his eye on the more prosperous island of Tobago, which Sweden had unsuccessfully attempted to colonise back in 1733, he ultimately settled for St Barts.

The Swedes set about developing St. Barts' main harbour and turned the city into a free port to facilitate Sweden's ability to participate in the flourishing West Indies economy.

"The port of Gustavia –named after Gustav III—attracted trade under different flags between North America, the West Indies, and Europe," Müller explains.

"Though St. Barts was unsuitable for agricultural products, its success was based on the free port idea."

While the island developed into a prosperous colony for about a half a century, transatlantic trade and the West Indies economy eventually collapsed in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars.

“There was a change in the economic structure. Perhaps the main reasons were that Europe started its own sugar production and newly independent Latin American states started developing their own economies,” says Müller.

Yellow fever also plagued the island, which was also battered by hurricanes, causing Sweden to rethink the colonial dreams it had pinned on its Caribbean colony.

In 1878, at the urging of parliament and following a referendum by the island's residents, Sweden's King Oscar II agreed to sell St. Barts back to the French for about 300,000 riksdaler, the equivalent of about 12 million kronor ($1.9 million) today.

Today, a steady flow of well-heeled international tourists has helped usher in an era of economic prosperity reminiscent of St. Barts' time as a bustling Swedish colony.

Despite its new found prosperity, the most chic island of the Caribbean is still working hard to rescue its Swedish heritage.

Although St. Barts is definitely a French island – most islanders are French-speaking descendants of the first settlers – its history under Swedish rule is reflected in many aspects of its culture and infrastructure.

Gustavia has retained its free port status, and many of the town's buildings feature Swedish architectural design from Sweden's colonial period.

In addition, the island’s coat of arms has the Swedish three crowns and official buildings still hoist both the French and the Swedish flags.

St. Barts resident Nils Dufau, president of the St. Barts Association of Friends of Sweden (ASBAS) explains that the island's ties to Sweden remain important to many residents.

"The islanders don’t want to neglect their Swedish heritage," he says.

As a child Dufau and his French-Swedish parents left Stockholm in a sail boat bound for the Caribbean.

After having lived many years in their boat, the family finally landed at St. Barts and decided to make it their home.

According to Dufau the best part of the island is that “everyone is treated as an equal. Even visitors can feel like a local over here!”

For years, Dufau has been the island’s Swedish spokesperson and a key figure in rescuing St. Barts' Swedish heritage.

“In February, we received new street name plates that we have specially ordered from a manufacturer in Sweden that manually produces enamel street signs," he gushes.

"Soon all our streets will be in both languages: Swedish and French!"

According to Dufau, it has become easier for islanders to celebrate their Swedish heritage since St. Barts became a separate entity from France in February 2007.

"We can make many more decisions on our own," he explains.

In addition, there is a "Gustavialoppet" marathon in November, which is celebrated throughout the island as "Swedish Month". The town of Piteå in northern Sweden has also had a twin-cities relationship with St. Barts for more than thirty years.

And for Swedes in the Caribbean feeling nostalgic for their motherland, the unofficial Swedish meeting place is Le Select, a restaurant-bar found on the corner of Nygatan and Östra Strandgatan in Gustavia.

“Swedes were friendly colonizers, they didn’t mistreat the locals. In this way, Sweden has no colonial guilt. It might be easier to be proud of a country’s history with this past,” says Müller.

Comments

See Also

The crystal blue waters, warm temperatures, and jet-setting tourists of Saint Barthélemy bear little resemblance to Sweden's forested landscape and sometimes bone-chilling climate.

When first hearing mention of this small Caribbean island with a French sounding name, commonly known as St. Barts, one is hard pressed to make any connection to Sweden whatsoever.

Discovered in 1493 by Christopher Columbus, who named it after his younger brother, this roughly 20 square kilometre patch of land was taken over by the French in 1648.

But in 1784, Sweden's King Gustav III managed to negotiate the acquisition of what would end up being Sweden's longest-held colony in the western hemisphere by offering France's Louis XVI warehousing rights in Gothenburg.

On March 7th, 1758, St. Barts officially became a Swedish colony, ushering in almost a century of Swedish rule.

According to Leos Müller, professor of marine history at Stockholm University, Gustav III had ambitious colonial dreams for Sweden.

Apart from commercial interests, Gustav III also had a big political agenda for his growing empire, believing a colony in the Caribbean would "confirm Sweden’s status among the great European nations", Müller explains.

While Gustav III had his eye on the more prosperous island of Tobago, which Sweden had unsuccessfully attempted to colonise back in 1733, he ultimately settled for St Barts.

The Swedes set about developing St. Barts' main harbour and turned the city into a free port to facilitate Sweden's ability to participate in the flourishing West Indies economy.

"The port of Gustavia –named after Gustav III—attracted trade under different flags between North America, the West Indies, and Europe," Müller explains.

"Though St. Barts was unsuitable for agricultural products, its success was based on the free port idea."

While the island developed into a prosperous colony for about a half a century, transatlantic trade and the West Indies economy eventually collapsed in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars.

“There was a change in the economic structure. Perhaps the main reasons were that Europe started its own sugar production and newly independent Latin American states started developing their own economies,” says Müller.

Yellow fever also plagued the island, which was also battered by hurricanes, causing Sweden to rethink the colonial dreams it had pinned on its Caribbean colony.

In 1878, at the urging of parliament and following a referendum by the island's residents, Sweden's King Oscar II agreed to sell St. Barts back to the French for about 300,000 riksdaler, the equivalent of about 12 million kronor ($1.9 million) today.

Today, a steady flow of well-heeled international tourists has helped usher in an era of economic prosperity reminiscent of St. Barts' time as a bustling Swedish colony.

Despite its new found prosperity, the most chic island of the Caribbean is still working hard to rescue its Swedish heritage.

Although St. Barts is definitely a French island – most islanders are French-speaking descendants of the first settlers – its history under Swedish rule is reflected in many aspects of its culture and infrastructure.

Gustavia has retained its free port status, and many of the town's buildings feature Swedish architectural design from Sweden's colonial period.

In addition, the island’s coat of arms has the Swedish three crowns and official buildings still hoist both the French and the Swedish flags.

St. Barts resident Nils Dufau, president of the St. Barts Association of Friends of Sweden (ASBAS) explains that the island's ties to Sweden remain important to many residents.

"The islanders don’t want to neglect their Swedish heritage," he says.

As a child Dufau and his French-Swedish parents left Stockholm in a sail boat bound for the Caribbean.

After having lived many years in their boat, the family finally landed at St. Barts and decided to make it their home.

According to Dufau the best part of the island is that “everyone is treated as an equal. Even visitors can feel like a local over here!”

For years, Dufau has been the island’s Swedish spokesperson and a key figure in rescuing St. Barts' Swedish heritage.

“In February, we received new street name plates that we have specially ordered from a manufacturer in Sweden that manually produces enamel street signs," he gushes.

"Soon all our streets will be in both languages: Swedish and French!"

According to Dufau, it has become easier for islanders to celebrate their Swedish heritage since St. Barts became a separate entity from France in February 2007.

"We can make many more decisions on our own," he explains.

In addition, there is a "Gustavialoppet" marathon in November, which is celebrated throughout the island as "Swedish Month". The town of Piteå in northern Sweden has also had a twin-cities relationship with St. Barts for more than thirty years.

And for Swedes in the Caribbean feeling nostalgic for their motherland, the unofficial Swedish meeting place is Le Select, a restaurant-bar found on the corner of Nygatan and Östra Strandgatan in Gustavia.

“Swedes were friendly colonizers, they didn’t mistreat the locals. In this way, Sweden has no colonial guilt. It might be easier to be proud of a country’s history with this past,” says Müller.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.