The Australian scientist stuck between a rock and a hard fika

What does an eccentric Swedish farmer have in common with an Australian paleontologist? No, it's not a Ross from Friends joke, it's about a petrified fern and a career in scientific research in Sweden.

"I've been interested in fossils ever since I was six or seven and used to dig up petrified wood on our pineapple farm north of Brisbane," Steve McLoughlin, senior curator at the Natural History Museum in Stockholm, tells The Local.

Seven years ago, he beat the competition for a research job in Sweden, where his partner lived. He says that for academics with such specialized research areas, a move to Sweden has to be about the right time, the right position. Otherwise, he personally would have struggled to find meaningful employment. Could he have moved without the job?

"Probably not, as I would have found it difficult to find another profession that suited me," he says.

For other academics, teaching can widen the field of job opportunity somewhat, but even so, it will come down the right time, and the right job for many academics who value their research specialities, he explains.

"My current position is quite ideal," he says. "It's one of the rare positions that gives you a great deal of freedom to do fundamental research and it's quite well funded."

The museum is currently recruiting for a similar position, and the dozens of applicants show the global nature of specialized research. Iraqis, Germans, Danes, Brits.

"This is quite a cosmopolitan workplace," McLoughlin says of the imposing museum perched on the outskirts of the capital.

But the cosmopolitanism comes at somewhat of a price, as he hasn't quite learned Swedish.

"Life's too short to spend enormous amounts of time learning multiple ways of saying the same thing," he says, although his pronunciation of Vetenskapsrådet - the council that allocates state funds for research - is spot on.

One thing remains resolutely Swedish about his workplace, however.

"The fascination with having meetings," he moans about talking over coffee, or fika. "Rather than delegate tasks you thrash it through around a table."

He sees the system's benefits, however, as well as its drawbacks.

"I find it takes time away from other tasks, but I guess it keeps the staff happy that they are participating in the decision-making process."

Sweden, he found when he arrived, had one major benefit over other countries - the relative ease of getting funding. But McLoughlin says that has changed.

"Funding has become very tight," he says. "Vetenskapsrådet has been directing money into a series of very specialized granting areas, which has made the general pool of funds smaller."

"At the moment, we're scrambling to write our next grant proposals," he says, as he and his colleagues now look both to the private sector and alternative grant sources such as National Geographic and The Friends of the Museum Society.

The time it all takes frustrates him, as every stab at getting more money takes up as much time as he would spend writing a full academic paper.

"So for every grant application, you're taking a paper off your CV," McLoughlin says.

Seven years ago, he estimates in retrospect, he felt one had a 25 to 30 percent chance of being awarded funds when you sent in your paperwork in Sweden. That has now shrunk to perhaps less than 20 - robbing Sweden of its easy funding appeal and putting it on par with McLoughlin's native Australia.

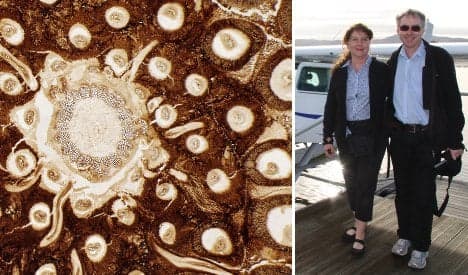

The paperwork aside, McLoughlin recently shot to kitchen table fame for his role in revealing "Sweden's Pompeii" to the world in the shape of a 180 million year-old fern. It had been sitting in a drawer in the museum until the researchers got back on its trail... an earlier curator at the museum had been studying the fossil - "he probably was about to publish" - when he died of skin cancer in the 1970s.

Re-examined, the specimen turned out to be, for lack of a more scientific term, awesome.

"It has the most remarkable internal preservation," McLoughlin explains. "You can see the individual nuclei and even within the nuclei there are sometimes chromosomes visible."

The story behind it demands a quick study.

It was found by a farmer in central Skåne, who was used to discovering fossils on his land but thought this one different. He sent the petrified stem off to Lund University, who dispatched a team of investigators. They, however, found nothing, which the farmer was informed of by letter.

"They knew the farmer was a bit eccentric, but they also knew he had a good eye for fossils, but when they found nothing they said they wouldn't be coming back... so the farmer was a bit annoyed," McLoughlin says.

"So he went down to the paddock with his pick and shovel, pulled up a lot more fossil wood and sent it to the Riksmuseet instead," he says with a raspy giggle.

Yet it took another four decades for the farmer's find to be examined properly.

"It's very robust, like limestone, so it didn't need any special conservation, it just stayed in a regular draw," McLoughlin says.

He explains that its level of preservation was due to how fast the volcanic mudflow buried the plants in the area, which 180 million years ago would have looked a bit like the hot-spring terrain of Yellowstone National Park in the US.

"Even, a bit like a Swedish Pompeii, where a whole bunch of ferns and plants were buried by a mud flow and covered in an ash deposit."

The only drawback, it seems, to McLoughlin's career in Sweden comes when he leaves the country to do fieldwork. Filling in the "profession" box on arrivals paperwork often sparks the same response from customs.

"You’re a palaeontologist! - Oh, like Ross from Friends."

Comments

See Also

"I've been interested in fossils ever since I was six or seven and used to dig up petrified wood on our pineapple farm north of Brisbane," Steve McLoughlin, senior curator at the Natural History Museum in Stockholm, tells The Local.

Seven years ago, he beat the competition for a research job in Sweden, where his partner lived. He says that for academics with such specialized research areas, a move to Sweden has to be about the right time, the right position. Otherwise, he personally would have struggled to find meaningful employment. Could he have moved without the job?

"Probably not, as I would have found it difficult to find another profession that suited me," he says.

For other academics, teaching can widen the field of job opportunity somewhat, but even so, it will come down the right time, and the right job for many academics who value their research specialities, he explains.

"My current position is quite ideal," he says. "It's one of the rare positions that gives you a great deal of freedom to do fundamental research and it's quite well funded."

The museum is currently recruiting for a similar position, and the dozens of applicants show the global nature of specialized research. Iraqis, Germans, Danes, Brits.

"This is quite a cosmopolitan workplace," McLoughlin says of the imposing museum perched on the outskirts of the capital.

But the cosmopolitanism comes at somewhat of a price, as he hasn't quite learned Swedish.

"Life's too short to spend enormous amounts of time learning multiple ways of saying the same thing," he says, although his pronunciation of Vetenskapsrådet - the council that allocates state funds for research - is spot on.

One thing remains resolutely Swedish about his workplace, however.

"The fascination with having meetings," he moans about talking over coffee, or fika. "Rather than delegate tasks you thrash it through around a table."

He sees the system's benefits, however, as well as its drawbacks.

"I find it takes time away from other tasks, but I guess it keeps the staff happy that they are participating in the decision-making process."

Sweden, he found when he arrived, had one major benefit over other countries - the relative ease of getting funding. But McLoughlin says that has changed.

"Funding has become very tight," he says. "Vetenskapsrådet has been directing money into a series of very specialized granting areas, which has made the general pool of funds smaller."

"At the moment, we're scrambling to write our next grant proposals," he says, as he and his colleagues now look both to the private sector and alternative grant sources such as National Geographic and The Friends of the Museum Society.

The time it all takes frustrates him, as every stab at getting more money takes up as much time as he would spend writing a full academic paper.

"So for every grant application, you're taking a paper off your CV," McLoughlin says.

Seven years ago, he estimates in retrospect, he felt one had a 25 to 30 percent chance of being awarded funds when you sent in your paperwork in Sweden. That has now shrunk to perhaps less than 20 - robbing Sweden of its easy funding appeal and putting it on par with McLoughlin's native Australia.

The paperwork aside, McLoughlin recently shot to kitchen table fame for his role in revealing "Sweden's Pompeii" to the world in the shape of a 180 million year-old fern. It had been sitting in a drawer in the museum until the researchers got back on its trail... an earlier curator at the museum had been studying the fossil - "he probably was about to publish" - when he died of skin cancer in the 1970s.

Re-examined, the specimen turned out to be, for lack of a more scientific term, awesome.

"It has the most remarkable internal preservation," McLoughlin explains. "You can see the individual nuclei and even within the nuclei there are sometimes chromosomes visible."

The story behind it demands a quick study.

It was found by a farmer in central Skåne, who was used to discovering fossils on his land but thought this one different. He sent the petrified stem off to Lund University, who dispatched a team of investigators. They, however, found nothing, which the farmer was informed of by letter.

"They knew the farmer was a bit eccentric, but they also knew he had a good eye for fossils, but when they found nothing they said they wouldn't be coming back... so the farmer was a bit annoyed," McLoughlin says.

"So he went down to the paddock with his pick and shovel, pulled up a lot more fossil wood and sent it to the Riksmuseet instead," he says with a raspy giggle.

Yet it took another four decades for the farmer's find to be examined properly.

"It's very robust, like limestone, so it didn't need any special conservation, it just stayed in a regular draw," McLoughlin says.

He explains that its level of preservation was due to how fast the volcanic mudflow buried the plants in the area, which 180 million years ago would have looked a bit like the hot-spring terrain of Yellowstone National Park in the US.

"Even, a bit like a Swedish Pompeii, where a whole bunch of ferns and plants were buried by a mud flow and covered in an ash deposit."

The only drawback, it seems, to McLoughlin's career in Sweden comes when he leaves the country to do fieldwork. Filling in the "profession" box on arrivals paperwork often sparks the same response from customs.

"You’re a palaeontologist! - Oh, like Ross from Friends."

Seven years ago, he beat the competition for a research job in Sweden, where his partner lived. He says that for academics with such specialized research areas, a move to Sweden has to be about the right time, the right position. Otherwise, he personally would have struggled to find meaningful employment. Could he have moved without the job?

"Probably not, as I would have found it difficult to find another profession that suited me," he says.

For other academics, teaching can widen the field of job opportunity somewhat, but even so, it will come down the right time, and the right job for many academics who value their research specialities, he explains.

"My current position is quite ideal," he says. "It's one of the rare positions that gives you a great deal of freedom to do fundamental research and it's quite well funded."

The museum is currently recruiting for a similar position, and the dozens of applicants show the global nature of specialized research. Iraqis, Germans, Danes, Brits.

"This is quite a cosmopolitan workplace," McLoughlin says of the imposing museum perched on the outskirts of the capital.

But the cosmopolitanism comes at somewhat of a price, as he hasn't quite learned Swedish.

"Life's too short to spend enormous amounts of time learning multiple ways of saying the same thing," he says, although his pronunciation of Vetenskapsrådet - the council that allocates state funds for research - is spot on.

One thing remains resolutely Swedish about his workplace, however.

"The fascination with having meetings," he moans about talking over coffee, or fika. "Rather than delegate tasks you thrash it through around a table."

He sees the system's benefits, however, as well as its drawbacks.

"I find it takes time away from other tasks, but I guess it keeps the staff happy that they are participating in the decision-making process."

Sweden, he found when he arrived, had one major benefit over other countries - the relative ease of getting funding. But McLoughlin says that has changed.

"Funding has become very tight," he says. "Vetenskapsrådet has been directing money into a series of very specialized granting areas, which has made the general pool of funds smaller."

"At the moment, we're scrambling to write our next grant proposals," he says, as he and his colleagues now look both to the private sector and alternative grant sources such as National Geographic and The Friends of the Museum Society.

The time it all takes frustrates him, as every stab at getting more money takes up as much time as he would spend writing a full academic paper.

"So for every grant application, you're taking a paper off your CV," McLoughlin says.

Seven years ago, he estimates in retrospect, he felt one had a 25 to 30 percent chance of being awarded funds when you sent in your paperwork in Sweden. That has now shrunk to perhaps less than 20 - robbing Sweden of its easy funding appeal and putting it on par with McLoughlin's native Australia.

The paperwork aside, McLoughlin recently shot to kitchen table fame for his role in revealing "Sweden's Pompeii" to the world in the shape of a 180 million year-old fern. It had been sitting in a drawer in the museum until the researchers got back on its trail... an earlier curator at the museum had been studying the fossil - "he probably was about to publish" - when he died of skin cancer in the 1970s.

Re-examined, the specimen turned out to be, for lack of a more scientific term, awesome.

"It has the most remarkable internal preservation," McLoughlin explains. "You can see the individual nuclei and even within the nuclei there are sometimes chromosomes visible."

The story behind it demands a quick study.

It was found by a farmer in central Skåne, who was used to discovering fossils on his land but thought this one different. He sent the petrified stem off to Lund University, who dispatched a team of investigators. They, however, found nothing, which the farmer was informed of by letter.

"They knew the farmer was a bit eccentric, but they also knew he had a good eye for fossils, but when they found nothing they said they wouldn't be coming back... so the farmer was a bit annoyed," McLoughlin says.

"So he went down to the paddock with his pick and shovel, pulled up a lot more fossil wood and sent it to the Riksmuseet instead," he says with a raspy giggle.

Yet it took another four decades for the farmer's find to be examined properly.

"It's very robust, like limestone, so it didn't need any special conservation, it just stayed in a regular draw," McLoughlin says.

He explains that its level of preservation was due to how fast the volcanic mudflow buried the plants in the area, which 180 million years ago would have looked a bit like the hot-spring terrain of Yellowstone National Park in the US.

"Even, a bit like a Swedish Pompeii, where a whole bunch of ferns and plants were buried by a mud flow and covered in an ash deposit."

The only drawback, it seems, to McLoughlin's career in Sweden comes when he leaves the country to do fieldwork. Filling in the "profession" box on arrivals paperwork often sparks the same response from customs.

"You’re a palaeontologist! - Oh, like Ross from Friends."

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.