Hold on tight: Sweden’s housing bubble has burst

House prices are falling like a stone. David Crouch asks what this means for householders and for the Swedish economy.

Nobody saw this coming. Everybody saw this coming. Sweden’s red-hot housing market, and the huge loans people took out to buy property, have been worrying economists and regulators for the best part of a decade.

After 17 years of dizzying growth, house prices are now falling like a stone. Barely 18 months ago, they were still rising at a crazy 20 percent a year. That rate of growth then slowed, and finally turned negative during the summer.

Prices are now falling rapidly, and the fall is accelerating. Prices have already dropped 14 percent from their peak, and the central bank estimates they will plunge by a total of 20 percent. Many economists say this scenario is optimistic. The truth is, nobody knows what’s going to happen.

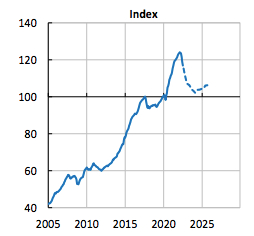

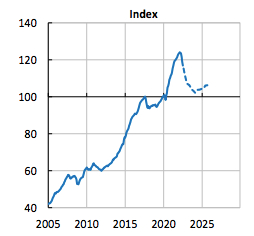

Yet everybody saw this coming. “It's like sitting on a volcano,” Stefan Ingves, the outgoing central bank governor, said last year about Sweden’s mountain of household debt. “I’ve been sitting on the volcano for many, many years,” he added. House prices trebled between 2005 and 2022, while levels of household debt soared to among the highest in the world.

Yet nobody saw this coming. When the pandemic hit, the central bank made it easier to take out a mortgage and encouraged the banks to carry on lending. The Moderate Party, whose leader is now prime minister, went to the polls promising to suspend the requirement for home-owners to pay back the principal on their loans, a measure which could only further fuel the bubble. (The government is now trying to wriggle off that particular hook.)

Sweden’s house price index has trebled and now gone into reverse. Source: Riksbanken

They said it couldn’t happen. House prices would become a problem only if inflation started to rise, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates. Impossible, said Stefan Ingves. In March 2021, he said Swedish inflation would not go above 2 percent. A year later, when it was 4 percent, he said this was “temporary” and it would not go any higher.

By September, inflation was almost 10 percent, the highest for decades. So the central bank slammed on the brakes and started raising rates. The bank’s main interest rate was hiked from zero in April to 2.5 percent today, and higher rates will follow, it says.

Suddenly, many Swedish households have seen their monthly bills shoot up. “I think people are a bit taken aback by the fact that their costs have risen so quickly,” a regional manager for Sparbanken Skåne told SVT last week. “We are seeing a lot of worry among our customers about the economy and the future.”

A vicious circle

Sweden’s housing bubble is part of a wider picture. House prices have “decoupled” from the rest economy, Europe’s financial watchdog warned early this year, picking out Sweden as one of the countries most at risk of a “brutal downturn”. Across the developed world, rock-bottom interest rates encouraged a mortgage binge with spiralling property prices.

The fear is a repeat of the 2008 global financial crisis, which started when housing loans turned bad in the United States. People could not repay their mortgages, banks could not sell their homes to recoup the loans, so banks stopped lending to businesses, businesses went bust, unemployment rose, more people couldn’t pay back their loans, and onward and downward it went in a vicious circle.

Back then, house prices in the rich countries fell by an average of 13 percent from their peak in 2007. In Greece, Italy and Spain, the housing crash was so extreme that prices are not yet back where they were 15 years ago.

Could something similar happen in Sweden? A key difference today is the strength of the global economy. Unemployment will not be so severe as it was in the wake of the financial crisis, the IMF expects. If people hold onto their jobs, there is a reasonable chance that the downturn in the housing market could be limited. In this same vein, Stefan Ingves told the Financial Times last month that the effect of the house price slump would be “manageable”, predicting merely a “reduction in consumption and investment”.

All the same, Sweden’s major banks are being instructed to prepare for the worst. There is an increased risk that they will suffer from large credit losses as people default on their loans, the central bank warned in its stability report last month. Finansinspektionen, Sweden’s Financial Supervisory Authority, is now requiring banks to build up their capital reserves.

Part of the problem that is specific to Sweden is that many here have variable mortgages, which jump up as soon as interest rates go up. In 2018, around 80% of Swedish mortgages had a variable rate. This has now fallen to around 30 percent as people have switched to fixed-rate mortgages that bind them into a steady repayment. But even this is double the Eurozone average and far higher than France, Germany and Belgium, where the proportion is lower than 10 percent.

With the war in Ukraine affecting energy and food supplies, inflation raging and widespread predictions of a global recession, who would confidently predict that Sweden’s housing crash will lead to the hoped-for “soft landing” with limited economic effects?

On the plus side, Sweden’s banks are strong: the four main banks are sitting on some 200 billion kronor in surplus capital. The country’s public finances are also healthy, which means Sweden can take measures to support house owners if things turn ugly. All the same, Finansinspektionen is advising the government against this. If you have problems paying your mortgage, it says, you need to speak to your bank and negotiate a reduced payment, rather than waiting for mortgage relief from the state.

However things pan out, some households with large mortgages – especially those who bought property near the peak of the bubble – will experience crippling financial pain, with all the misery that brings. No soothing reassurances from central bankers can hide this fact. The brunt of responsibility must be borne by the centre-right and centre-left governments who sat on their hands during two decades when population growth greatly outstripped the housing supply, creating the massive demand for homes that caused the house price bubble.

Meanwhile, people who bought early in the housing boom have grown rich by doing nothing except living in their homes, the price of which has trebled. To all the Swedes struggling in crowded and rented accommodation, to all the young families priced out of the housing market, this represents a grossly unfair and undeserved transfer of wealth.

Now the bubble has burst, and we are all going to pay for it. Hold on tight – it could be a bumpy ride.

David Crouch is the author of Almost Perfekt: How Sweden Works and What Can We Learn From It. He is a freelance journalist and a lecturer in journalism at Gothenburg University

Comments

See Also

Nobody saw this coming. Everybody saw this coming. Sweden’s red-hot housing market, and the huge loans people took out to buy property, have been worrying economists and regulators for the best part of a decade.

After 17 years of dizzying growth, house prices are now falling like a stone. Barely 18 months ago, they were still rising at a crazy 20 percent a year. That rate of growth then slowed, and finally turned negative during the summer.

Prices are now falling rapidly, and the fall is accelerating. Prices have already dropped 14 percent from their peak, and the central bank estimates they will plunge by a total of 20 percent. Many economists say this scenario is optimistic. The truth is, nobody knows what’s going to happen.

Yet everybody saw this coming. “It's like sitting on a volcano,” Stefan Ingves, the outgoing central bank governor, said last year about Sweden’s mountain of household debt. “I’ve been sitting on the volcano for many, many years,” he added. House prices trebled between 2005 and 2022, while levels of household debt soared to among the highest in the world.

Yet nobody saw this coming. When the pandemic hit, the central bank made it easier to take out a mortgage and encouraged the banks to carry on lending. The Moderate Party, whose leader is now prime minister, went to the polls promising to suspend the requirement for home-owners to pay back the principal on their loans, a measure which could only further fuel the bubble. (The government is now trying to wriggle off that particular hook.)

They said it couldn’t happen. House prices would become a problem only if inflation started to rise, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates. Impossible, said Stefan Ingves. In March 2021, he said Swedish inflation would not go above 2 percent. A year later, when it was 4 percent, he said this was “temporary” and it would not go any higher.

By September, inflation was almost 10 percent, the highest for decades. So the central bank slammed on the brakes and started raising rates. The bank’s main interest rate was hiked from zero in April to 2.5 percent today, and higher rates will follow, it says.

Suddenly, many Swedish households have seen their monthly bills shoot up. “I think people are a bit taken aback by the fact that their costs have risen so quickly,” a regional manager for Sparbanken Skåne told SVT last week. “We are seeing a lot of worry among our customers about the economy and the future.”

A vicious circle

Sweden’s housing bubble is part of a wider picture. House prices have “decoupled” from the rest economy, Europe’s financial watchdog warned early this year, picking out Sweden as one of the countries most at risk of a “brutal downturn”. Across the developed world, rock-bottom interest rates encouraged a mortgage binge with spiralling property prices.

The fear is a repeat of the 2008 global financial crisis, which started when housing loans turned bad in the United States. People could not repay their mortgages, banks could not sell their homes to recoup the loans, so banks stopped lending to businesses, businesses went bust, unemployment rose, more people couldn’t pay back their loans, and onward and downward it went in a vicious circle.

Back then, house prices in the rich countries fell by an average of 13 percent from their peak in 2007. In Greece, Italy and Spain, the housing crash was so extreme that prices are not yet back where they were 15 years ago.

Could something similar happen in Sweden? A key difference today is the strength of the global economy. Unemployment will not be so severe as it was in the wake of the financial crisis, the IMF expects. If people hold onto their jobs, there is a reasonable chance that the downturn in the housing market could be limited. In this same vein, Stefan Ingves told the Financial Times last month that the effect of the house price slump would be “manageable”, predicting merely a “reduction in consumption and investment”.

All the same, Sweden’s major banks are being instructed to prepare for the worst. There is an increased risk that they will suffer from large credit losses as people default on their loans, the central bank warned in its stability report last month. Finansinspektionen, Sweden’s Financial Supervisory Authority, is now requiring banks to build up their capital reserves.

Part of the problem that is specific to Sweden is that many here have variable mortgages, which jump up as soon as interest rates go up. In 2018, around 80% of Swedish mortgages had a variable rate. This has now fallen to around 30 percent as people have switched to fixed-rate mortgages that bind them into a steady repayment. But even this is double the Eurozone average and far higher than France, Germany and Belgium, where the proportion is lower than 10 percent.

With the war in Ukraine affecting energy and food supplies, inflation raging and widespread predictions of a global recession, who would confidently predict that Sweden’s housing crash will lead to the hoped-for “soft landing” with limited economic effects?

On the plus side, Sweden’s banks are strong: the four main banks are sitting on some 200 billion kronor in surplus capital. The country’s public finances are also healthy, which means Sweden can take measures to support house owners if things turn ugly. All the same, Finansinspektionen is advising the government against this. If you have problems paying your mortgage, it says, you need to speak to your bank and negotiate a reduced payment, rather than waiting for mortgage relief from the state.

However things pan out, some households with large mortgages – especially those who bought property near the peak of the bubble – will experience crippling financial pain, with all the misery that brings. No soothing reassurances from central bankers can hide this fact. The brunt of responsibility must be borne by the centre-right and centre-left governments who sat on their hands during two decades when population growth greatly outstripped the housing supply, creating the massive demand for homes that caused the house price bubble.

Meanwhile, people who bought early in the housing boom have grown rich by doing nothing except living in their homes, the price of which has trebled. To all the Swedes struggling in crowded and rented accommodation, to all the young families priced out of the housing market, this represents a grossly unfair and undeserved transfer of wealth.

Now the bubble has burst, and we are all going to pay for it. Hold on tight – it could be a bumpy ride.

David Crouch is the author of Almost Perfekt: How Sweden Works and What Can We Learn From It. He is a freelance journalist and a lecturer in journalism at Gothenburg University

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.