KEY POINTS: The final verdict on Sweden's Covid-19 response

Sweden's decision to rely on voluntary measures rather than a strict lockdown to handle the Covid-19 pandemic was "fundamentally correct", but its measures were too weak and too late, the final report by the Coronavirus Commission concludes.

In its final conclusions, the commission – established in June 2020 and chaired by the judge Mats Melin – gives perhaps unexpectedly strong support for Sweden's choice of strategy, based on its previous reports.

"The state should not limit the freedom of the individual more than is necessary," Melin said at a press conference announcing the conclusions. "But -- and this is an important 'but' -- more far-reaching measures can be necessary in certain situations."

In its final report, the commission concludes that "the choice of path in terms of disease prevention and control, focusing on advice and recommendations which people were expected to follow voluntarily, was fundamentally correct".

Not imposing coercive measures meant that citizens "retained more of their personal freedom than in many other countries."

In addition, the commission concludes, it is "not convinced that extended or recurring mandatory lockdowns, as introduced in other countries, are a necessary element in the response to a new, serious epidemic outbreak".

Several countries which did impose lockdowns, it points out, had "significantly worse outcomes" than Sweden, while the restriction of individual freedom was "hardly defensible other than in the face of very extreme threats".

Too little, too late

The commission is, however, more critical of the way Sweden's no-lockdown strategy was implemented.

"The measures taken were too few and should have come sooner," it concludes. "In February/March 2020, Sweden should have opted for more rigorous and intrusive disease prevention and control measures."

These, the commission argues, should have included most "indoor settings where people gather or come into close contact", including shopping centres, restaurants, cultural and sports events, hairdressing salons, and swimming pools.

In particular, the commission says it is "remarkable" that it took until March 29th for Sweden to reduce the maximum number of people allowed to meet for indoor events to 50.

The government was right, however, to allow schools to remain open for physical tuition.

"In the absence of a plan to protect older people and other at-risk groups, earlier and additional steps should have been taken to try to slow community transmission of the virus. Such initial measures would also have bought more time for overview and analysis."

Face masks, border controls, and quarantine should have been used earlier

The commission argues that the government should have asked those returning from ski trips in Italy and elsewhere at the end of February and the start of March to go into home quarantine for a week, as it was already clear that those travelling for ski holidays from other countries were returning home infected.

It also believes that the government should have followed Denmark and Norway and instituted a temporary entry ban for all but the most essential travel in mid-March, which would have both reduced the influx of infected people and also made it easier to align Sweden's border controls with those of its neighbours.

When it comes to the vexed question of face masks, the commission agrees that initial shortages justified not recommending them at the start of the pandemic, but argues that as soon as they were available they should have been recommended in crowded public places.

"Face masks should not have been categorically rejected as an infection control measure," Melin said in a press conference. "We believe that the fact that this was done contributed to the low level of adoption when the Public Health Agency eventually changed position on the issue."

Too little leadership from the government

The report is also critical of the way the government passed most of the responsibility for setting the strategy, handling the pandemic, and communicating with the public to the Public Health Agency, its then director-general Johan Carlson, and Sweden's state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell.

Rather than falling back on the Swedish tradition of leaving agencies to carry out their function without detailed "ministerial control", it believes the government could and should have seized control of the pandemic response, and of communicating with the public.

"The Government should have assumed leadership of all aspects of crisis management from the outset," it said. "It should have been able to overcome the obstacles to clear national leadership that currently exist."

It also accuses the government of being over-reliant on the Public Health Agency's expertise, and of doing too little to counter this by soliciting information from other scientists and disease control experts.

"The Government had too one-sided a dependence on assessments made by the Public Health Agency of Sweden," it concludes. "Responsibility for those assessments ultimately rests on a single person, the agency’s director-general. This is not a satisfactory arrangement for decision-making during a serious crisis in society."

Measures suited for educated middle class

The commission notes that disadvantaged groups have been hit hardest by Covid-19, something it puts down to measures best suited to well-educated middle class people in jobs that allow them to work from home.

Those working in jobs such as care work, the health sector, the service sector, and education, were less able to protect themselves, it argues. In addition, those without a car had to use public transport, while elderly people sharing crowded apartments with their children and grandchildren, could not isolate themselves.

"The measures introduced have thus often been better suited to a well-educated middle class, well placed to protect themselves from infection, navigate the health care system and work from home," it concludes. "Different measures may be needed to safeguard the lives and livelihoods of groups with more limited options."

How badly was Sweden hit by the pandemic compared to other countries?

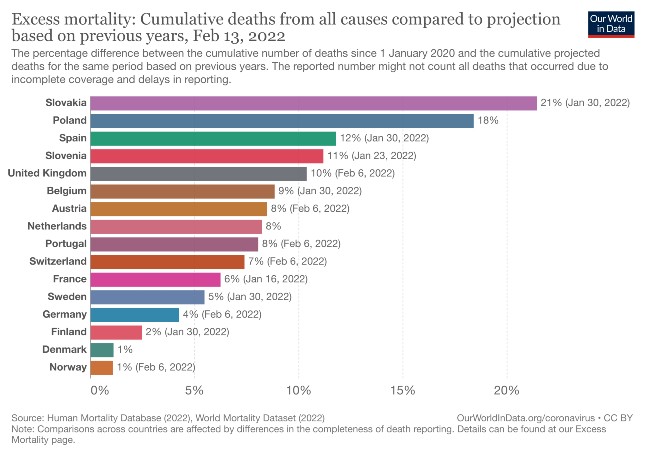

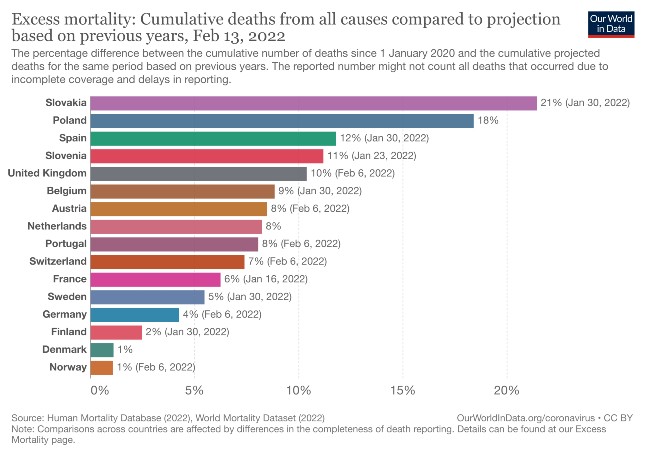

In the report, the commission notes that Sweden is among the country's who have suffered the lowest levels of excess mortality during 2020-2021.

Judging by the chart below, from Our World in Data, the number of deaths in Sweden were about five percent higher than would have been expected during the period, better than every country in Europe apart from Norway, Denmark, Finland and Germany.

But the report pointed out that this was not the case at all points during the pandemic.

"To learn the right lessons, we should not forget the way the situation looked in the spring of 2020, when Sweden at times had one of the highest death rates in Europe. Many people had to die without having a loved one or any other person at all by their side."

Who is to blame for the shortcomings?

The commission argues that Sweden's slow response came partly because the Public Health Agency "adopted a position informed by a demand for evidence -- rather than a precautionary approach".

The agency, it believes, "had a defensive view of the prospects of slowing the spread of the virus" and as a result "introduced and advocated limited, late and not very vigorous measures".

For this, it concludes, the agency’s then director-general, Johan Carlson, is to blame.

But neither the government, nor the then Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, gets off the hook.

"We consider that the government of 2020 and Prime Minister Stefan Löfven is responsible for having accepted largely uncritically, right up to the late autumn of 2020, the assessments of its expert agency." Melin said during the press conference.

The prime minister had also, he added, failed "to issue directives calling on the agency to correct its course."

Documentation the commission has received, he added, showed Löfven in October 2020 then belatedly taking action to take more control.

"The government let the Public Health Agency hold the baton for a long period," Melin said, "right up to the cusp between October and November 2020."

What are the commission's recommendations?

The commission makes a series of recommendations, from the obvious, such as the need to be better prepared in future, to calls for thoroughgoing administrative reform.

The commission calls for the establishment of a "new, centrally located body with substantial powers, reporting directly to the government", for managing peacetime crises.

"This body would be able to obtain information from all relevant stakeholders, lay down clear guidelines for their work, and where necessary, when it is not possible to await a government decision, issue binding directives to public authorities to carry out a measure judged to be necessary."

The committee also calls for a "precautionary principle" to be explicitly instated in Sweden's crisis management system,

"The principle implies that...decision-makers should not passively wait for a better understanding, but actively take steps to counter the threat. It means, in other words, that it is better to act than to wait for better data for decision-making."

It calls for a cross-party committee to be established to work out how to make these changes to Sweden's crisis management system.

Finally, it calls for reform to Sweden's disease prevention and control framework to be reorganised so that the Public Health Agency no longer has sole responsibility for providing the government with data to support its decision-making, with arrangements in place to bring in a variety of different epidemiological viewpoints.

Comments (1)

See Also

In its final conclusions, the commission – established in June 2020 and chaired by the judge Mats Melin – gives perhaps unexpectedly strong support for Sweden's choice of strategy, based on its previous reports.

"The state should not limit the freedom of the individual more than is necessary," Melin said at a press conference announcing the conclusions. "But -- and this is an important 'but' -- more far-reaching measures can be necessary in certain situations."

In its final report, the commission concludes that "the choice of path in terms of disease prevention and control, focusing on advice and recommendations which people were expected to follow voluntarily, was fundamentally correct".

Not imposing coercive measures meant that citizens "retained more of their personal freedom than in many other countries."

In addition, the commission concludes, it is "not convinced that extended or recurring mandatory lockdowns, as introduced in other countries, are a necessary element in the response to a new, serious epidemic outbreak".

Several countries which did impose lockdowns, it points out, had "significantly worse outcomes" than Sweden, while the restriction of individual freedom was "hardly defensible other than in the face of very extreme threats".

Too little, too late

The commission is, however, more critical of the way Sweden's no-lockdown strategy was implemented.

"The measures taken were too few and should have come sooner," it concludes. "In February/March 2020, Sweden should have opted for more rigorous and intrusive disease prevention and control measures."

These, the commission argues, should have included most "indoor settings where people gather or come into close contact", including shopping centres, restaurants, cultural and sports events, hairdressing salons, and swimming pools.

In particular, the commission says it is "remarkable" that it took until March 29th for Sweden to reduce the maximum number of people allowed to meet for indoor events to 50.

The government was right, however, to allow schools to remain open for physical tuition.

"In the absence of a plan to protect older people and other at-risk groups, earlier and additional steps should have been taken to try to slow community transmission of the virus. Such initial measures would also have bought more time for overview and analysis."

Face masks, border controls, and quarantine should have been used earlier

The commission argues that the government should have asked those returning from ski trips in Italy and elsewhere at the end of February and the start of March to go into home quarantine for a week, as it was already clear that those travelling for ski holidays from other countries were returning home infected.

It also believes that the government should have followed Denmark and Norway and instituted a temporary entry ban for all but the most essential travel in mid-March, which would have both reduced the influx of infected people and also made it easier to align Sweden's border controls with those of its neighbours.

When it comes to the vexed question of face masks, the commission agrees that initial shortages justified not recommending them at the start of the pandemic, but argues that as soon as they were available they should have been recommended in crowded public places.

"Face masks should not have been categorically rejected as an infection control measure," Melin said in a press conference. "We believe that the fact that this was done contributed to the low level of adoption when the Public Health Agency eventually changed position on the issue."

Too little leadership from the government

The report is also critical of the way the government passed most of the responsibility for setting the strategy, handling the pandemic, and communicating with the public to the Public Health Agency, its then director-general Johan Carlson, and Sweden's state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell.

Rather than falling back on the Swedish tradition of leaving agencies to carry out their function without detailed "ministerial control", it believes the government could and should have seized control of the pandemic response, and of communicating with the public.

"The Government should have assumed leadership of all aspects of crisis management from the outset," it said. "It should have been able to overcome the obstacles to clear national leadership that currently exist."

It also accuses the government of being over-reliant on the Public Health Agency's expertise, and of doing too little to counter this by soliciting information from other scientists and disease control experts.

"The Government had too one-sided a dependence on assessments made by the Public Health Agency of Sweden," it concludes. "Responsibility for those assessments ultimately rests on a single person, the agency’s director-general. This is not a satisfactory arrangement for decision-making during a serious crisis in society."

Measures suited for educated middle class

The commission notes that disadvantaged groups have been hit hardest by Covid-19, something it puts down to measures best suited to well-educated middle class people in jobs that allow them to work from home.

Those working in jobs such as care work, the health sector, the service sector, and education, were less able to protect themselves, it argues. In addition, those without a car had to use public transport, while elderly people sharing crowded apartments with their children and grandchildren, could not isolate themselves.

"The measures introduced have thus often been better suited to a well-educated middle class, well placed to protect themselves from infection, navigate the health care system and work from home," it concludes. "Different measures may be needed to safeguard the lives and livelihoods of groups with more limited options."

How badly was Sweden hit by the pandemic compared to other countries?

In the report, the commission notes that Sweden is among the country's who have suffered the lowest levels of excess mortality during 2020-2021.

Judging by the chart below, from Our World in Data, the number of deaths in Sweden were about five percent higher than would have been expected during the period, better than every country in Europe apart from Norway, Denmark, Finland and Germany.

But the report pointed out that this was not the case at all points during the pandemic.

"To learn the right lessons, we should not forget the way the situation looked in the spring of 2020, when Sweden at times had one of the highest death rates in Europe. Many people had to die without having a loved one or any other person at all by their side."

Who is to blame for the shortcomings?

The commission argues that Sweden's slow response came partly because the Public Health Agency "adopted a position informed by a demand for evidence -- rather than a precautionary approach".

The agency, it believes, "had a defensive view of the prospects of slowing the spread of the virus" and as a result "introduced and advocated limited, late and not very vigorous measures".

For this, it concludes, the agency’s then director-general, Johan Carlson, is to blame.

But neither the government, nor the then Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, gets off the hook.

"We consider that the government of 2020 and Prime Minister Stefan Löfven is responsible for having accepted largely uncritically, right up to the late autumn of 2020, the assessments of its expert agency." Melin said during the press conference.

The prime minister had also, he added, failed "to issue directives calling on the agency to correct its course."

Documentation the commission has received, he added, showed Löfven in October 2020 then belatedly taking action to take more control.

"The government let the Public Health Agency hold the baton for a long period," Melin said, "right up to the cusp between October and November 2020."

What are the commission's recommendations?

The commission makes a series of recommendations, from the obvious, such as the need to be better prepared in future, to calls for thoroughgoing administrative reform.

The commission calls for the establishment of a "new, centrally located body with substantial powers, reporting directly to the government", for managing peacetime crises.

"This body would be able to obtain information from all relevant stakeholders, lay down clear guidelines for their work, and where necessary, when it is not possible to await a government decision, issue binding directives to public authorities to carry out a measure judged to be necessary."

The committee also calls for a "precautionary principle" to be explicitly instated in Sweden's crisis management system,

"The principle implies that...decision-makers should not passively wait for a better understanding, but actively take steps to counter the threat. It means, in other words, that it is better to act than to wait for better data for decision-making."

It calls for a cross-party committee to be established to work out how to make these changes to Sweden's crisis management system.

Finally, it calls for reform to Sweden's disease prevention and control framework to be reorganised so that the Public Health Agency no longer has sole responsibility for providing the government with data to support its decision-making, with arrangements in place to bring in a variety of different epidemiological viewpoints.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.