Politics in Sweden: Is the Green Party's past to blame for its current problems?

Per Gahrton, the founder of Sweden's Green Party, has died aged 80, leaving his party still struggling with many of the identity and organisational issues he bequeathed it, writes The Local's Nordic editor Richard Orange.

Per Gahrton, the scruffy, eccentric, uncompromising, and intellectually gifted MP who broke away from Sweden's Liberals to found the country's Green Party, has died, aged 80.

His death comes at a time when the party he founded is struggling.

The party is polling persistently near to the 4 percent threshold to enter parliament, something that is a bit of a mystery, given the extent to which current government's policies are sabotaging Sweden's chances of meeting climate goals which most Swedes think are important.

A lot the explanation goes back to Gahrton and his founding of the party in 1981.

Gahrton was never chiefly an environmental activist, but a politician with a broad liberal-left agenda, with strong views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, on sexual freedom, on gender equality.

For him, the problem with the modern economic model and its ideology of perpetual growth, was as much about its impact on the individual and society as on the environment, and the Social Democrats, as proponents of industrial socialism, were at least as big a part of the problem as right-wing proponents of industrial capitalism.

He spotted the opportunity, in the aftermath of the 1980 referendum on nuclear power, to harness support from the losing anti-nuclear campaign to form a new party, entering parliament in 1988 in the wake of the Chernobyl disaster.

But he was never primarily an anti-nuclear activist.

He was also an anti-politician, viewing party politics, with its compromises, hypocrisies and strategising, as dishonest and empty. This was part of the reason why the party, at its founding meeting, voted not to have a traditional leader but to instead be run by a political committee, with two spokespersons – one male and one female – who could at first not be active MPs.

Fully 42 years later, the party is still struggling with Gahrton's legacy.

It has never escaped Gahrton's scatter-gun approach to become a single-issue environmental party, instead burning political capital on its open migration policy, on education under Gustav Fridolin, or on integration and combating the far-right under Märta Stenevi.

As it was not founded as the political wing of the environment movement, it has never won the movement's broad support, so while Sweden's blue-collar unions will back the Social Democrats even when they compromise, environmental groups more often accuse the Green Party of betrayal.

While it has become a party of the liberal left, its origin as a breakaway from the liberal Folkpartiet means it has never been trusted by its allies in the Social Democrats and Left Party.

When in government between 2014 and 2021, the party became less scruffy and more practical, with clean-cut politicians like Fridolin, Isabella Lövin and Per Bolund focusing on the policy detail, on getting through concrete reforms to reduce emissions and protect the environment.

But they were always hobbled by the split between two spokespeople, which meant that each of the party's leaders only ever got half the air-time of their counterparts in other, similarly sized parties.

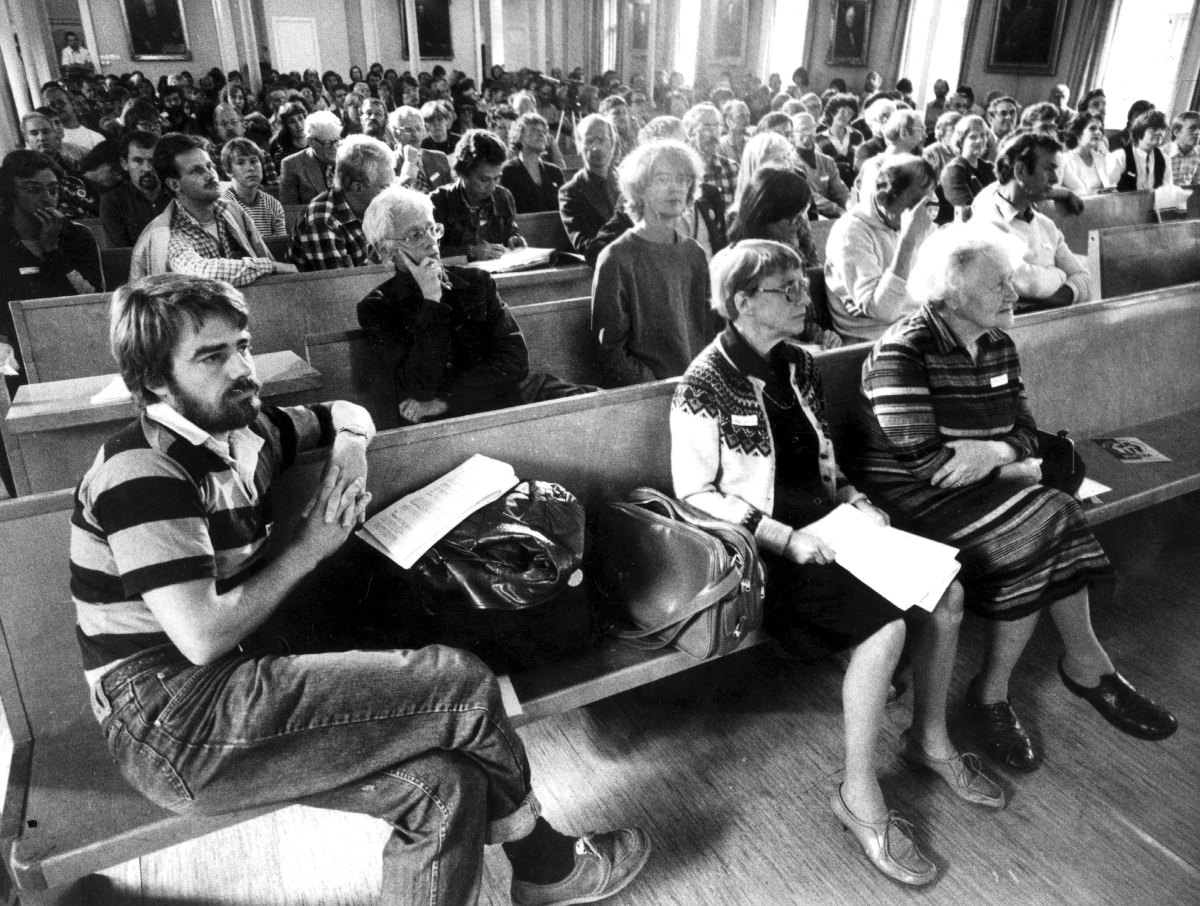

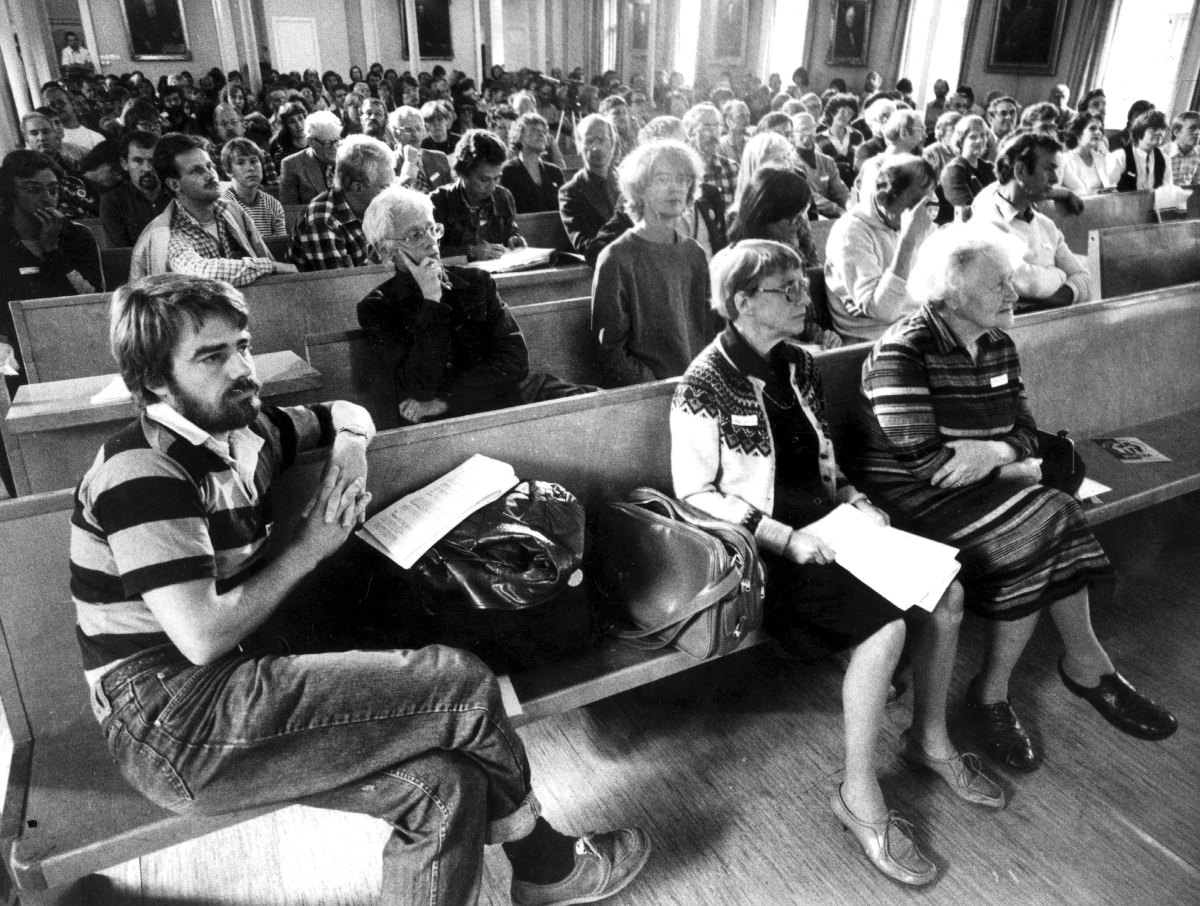

The Green Party at a meeting in Örebro in 1981. Sitting left is Per Gahrton. Photo: Andi Loor/Scanpix

Last Friday, after a long internal debate, the Green Party voted narrowly to keep this unwieldy two-spokesperson system, despite its youth wing calling for the party to move to a single leader.

The various wings of the party are now jockeying over who will be voted in to replace the outgoing spokesperson, Bolund, at the party's congress in mid-November.

Will it be Daniel Helldén, who is distrusted by the party's left for his decision to go into coalition with the conservative Moderate party to become Stockholm's transport councillor, and who wants a tighter focus on environmental issues? Will it be Pär Holmgren, the former TV weather man, again promising a tighter focus on climate change?

Or could it be Martin Marmgren, the serving police officer who wants to combat populistic approaches to immigration and criminal justice? Or Henrik Blind, the councillor from Jokkmokk, a member of the indigenous Sami people from northern Sweden, who would increase the party's focus on indigenous rights.

Each of these figures will have to wrestle in their own ways with the difficult questions Gahrton has left as his legacy.

Politics in Sweden is a weekly column looking at the big talking points and issues in Swedish politics. Members of The Local Sweden can sign up to receive an email alert when the column is published. Just click on this “newsletters" option or visit the menu bar.

Comments

See Also

Per Gahrton, the scruffy, eccentric, uncompromising, and intellectually gifted MP who broke away from Sweden's Liberals to found the country's Green Party, has died, aged 80.

His death comes at a time when the party he founded is struggling.

The party is polling persistently near to the 4 percent threshold to enter parliament, something that is a bit of a mystery, given the extent to which current government's policies are sabotaging Sweden's chances of meeting climate goals which most Swedes think are important.

A lot the explanation goes back to Gahrton and his founding of the party in 1981.

Gahrton was never chiefly an environmental activist, but a politician with a broad liberal-left agenda, with strong views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, on sexual freedom, on gender equality.

For him, the problem with the modern economic model and its ideology of perpetual growth, was as much about its impact on the individual and society as on the environment, and the Social Democrats, as proponents of industrial socialism, were at least as big a part of the problem as right-wing proponents of industrial capitalism.

He spotted the opportunity, in the aftermath of the 1980 referendum on nuclear power, to harness support from the losing anti-nuclear campaign to form a new party, entering parliament in 1988 in the wake of the Chernobyl disaster.

But he was never primarily an anti-nuclear activist.

He was also an anti-politician, viewing party politics, with its compromises, hypocrisies and strategising, as dishonest and empty. This was part of the reason why the party, at its founding meeting, voted not to have a traditional leader but to instead be run by a political committee, with two spokespersons – one male and one female – who could at first not be active MPs.

Fully 42 years later, the party is still struggling with Gahrton's legacy.

It has never escaped Gahrton's scatter-gun approach to become a single-issue environmental party, instead burning political capital on its open migration policy, on education under Gustav Fridolin, or on integration and combating the far-right under Märta Stenevi.

As it was not founded as the political wing of the environment movement, it has never won the movement's broad support, so while Sweden's blue-collar unions will back the Social Democrats even when they compromise, environmental groups more often accuse the Green Party of betrayal.

While it has become a party of the liberal left, its origin as a breakaway from the liberal Folkpartiet means it has never been trusted by its allies in the Social Democrats and Left Party.

When in government between 2014 and 2021, the party became less scruffy and more practical, with clean-cut politicians like Fridolin, Isabella Lövin and Per Bolund focusing on the policy detail, on getting through concrete reforms to reduce emissions and protect the environment.

But they were always hobbled by the split between two spokespeople, which meant that each of the party's leaders only ever got half the air-time of their counterparts in other, similarly sized parties.

Last Friday, after a long internal debate, the Green Party voted narrowly to keep this unwieldy two-spokesperson system, despite its youth wing calling for the party to move to a single leader.

The various wings of the party are now jockeying over who will be voted in to replace the outgoing spokesperson, Bolund, at the party's congress in mid-November.

Will it be Daniel Helldén, who is distrusted by the party's left for his decision to go into coalition with the conservative Moderate party to become Stockholm's transport councillor, and who wants a tighter focus on environmental issues? Will it be Pär Holmgren, the former TV weather man, again promising a tighter focus on climate change?

Or could it be Martin Marmgren, the serving police officer who wants to combat populistic approaches to immigration and criminal justice? Or Henrik Blind, the councillor from Jokkmokk, a member of the indigenous Sami people from northern Sweden, who would increase the party's focus on indigenous rights.

Each of these figures will have to wrestle in their own ways with the difficult questions Gahrton has left as his legacy.

Politics in Sweden is a weekly column looking at the big talking points and issues in Swedish politics. Members of The Local Sweden can sign up to receive an email alert when the column is published. Just click on this “newsletters" option or visit the menu bar.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.