Why are Sweden and Germany going opposite ways on labour migration?

While Sweden's government is making it harder for foreign workers to get residency permits, Germany's and Denmark's are making it easier. Why the difference and what's the likely impact?

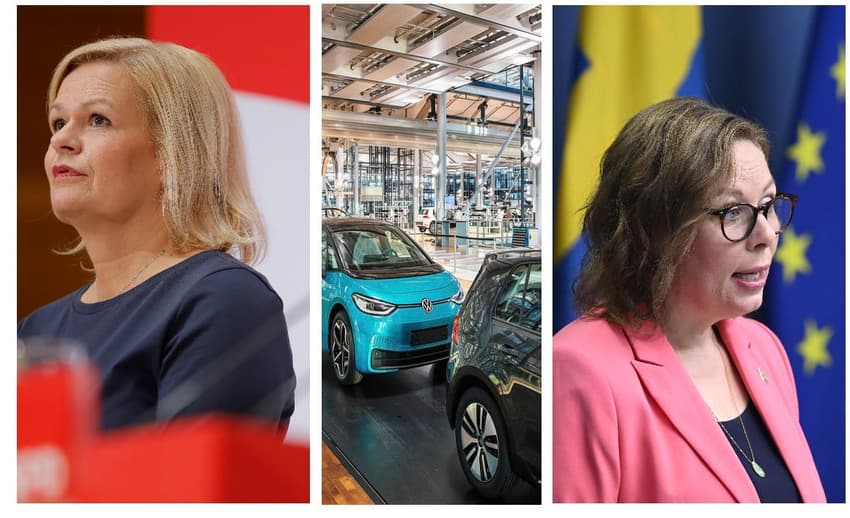

Germany is about to get "the most modern immigration law in the world", the country's interior minister, Nancy Faeser, boasted in June as her government introduced a bill to make it much easier for skilled workers to enter the country.

“This is a wish that has been expressed by large parts of the Danish business community in recent years,” explained Denmark's economy minister, Troels Lund Poulsen, as his government tabled its own bill to cut the minimum wage required for a key work permit scheme.

With a shortage of skilled labour hitting businesses across Europe, these countries' governments are taking action to make it easier for companies to hire from outside the European Union.

But Sweden is going in the opposite direction.

In three weeks' time, the minimum salary to be eligible for a work permit in Sweden will more than double, going from 13,000 kronor a month to at least 80 percent of the median salary, or 27,360 kronor a month (or more for jobs where the industry standard is higher than that). In January, an inquiry is expected to propose how to raise it all the way to the median salary, currently 34,200 kronor.

Sweden's export-driven economy is competing for much the same engineering and IT expertise as Germany's and Denmark's, and its businesses are similarly affected by shortages of skilled labour.

So why the difference?

The main reason is political, argues Tove Hovemyr, social policy expert at the liberal thinktank Fores.

"We have now a government that is supported by and very much dependent on the [far-right] Sweden Democrats' support, and they have to make nice with the party itself, but also try to steal their voters," she explained. "Right now everyone is terrified of looking somewhat pro-migration, and that's why the debates in Sweden and in Denmark and Germany are so vastly different."

The only parties still advocating a liberal labour migration in Sweden, she said, were the Centre Party and the Green Party.

Germany's new government, like Sweden's, promised a "paradigm shift on migration" in the deal between the coalition parties. But while Sweden's agreement promised to bring in the EU's toughest migration law, Germany's promised liberalisation.

In their coalition agreement, the three parties in Germany's new government promised "a new start for migration and integration policy", with would "accelerate and digitise the issue of visas", and which would "enable transnational labour migration" by allowing labour migrants to leave Germany for longer without their residency being at risk.

In Denmark, meanwhile, the decision of the traditional parties of right and left to go into coalition has made the current government the first in 20 years which is under little pressure to tighten immigration rules.

What is unusual in Sweden is that the business lobby, which has traditionally supported the ruling Moderate Party, is opposed to its plans for tighter labour migration.

Hovemyr dismissed Sweden's government's claims that it was making recruitment easier for highly skilled positions by ordering the Migration Agency to reform the work permit process.

"I think that is a way to justify to themselves and to their voters that they're making this policy shift, but no one is happy about it," she said. "Even those who are normally happy with the Moderates and the Liberals governing the country are now very angry about this policy shift."

EXPLAINED:

A recent study by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise estimated that the planned changes to the minimum salary requirement would cut Sweden's GDP by 16 billion kronor and lose the government a total of 5 billion kronor in tax revenues.

"There's a lot of companies that are frustrated now, asking 'how are we going to deal with this?" Patrik Karlsson, a recruitment policy expert at the organisation, told The Local. "They are not happy about it."

He said that Swedish businesses were also facing shortages of labour, and of skilled labour in particular, but said that in Denmark and Germany, politicians were also looking at long-term demographics.

"They see also that from a demographic perspective that they need to strengthen their attractiveness because they in the near future, the demographic analysis indicated that the labour force is going to shrink."

He conceded, though, that Sweden was tightening labour migration policy after 15 years of a system under which employers were able to recruit anyone internationally they wanted so long as they offered pay and benefit levels in line with union collective bargain agreements.

"Our laws on labour migration have been more liberal than in Denmark and Germany, so we were a bit ahead of them in that sense, and now Germany and Denmark have made the same analysis that we did 15 years ago, that we need more foreign talent."

Together with the large number of refugees Sweden received in 2014 and 2015, this period of liberal migration has left Sweden with a better demographic profile, with the labour force expected to increase slightly over the coming decade, after which Sweden again faces an imbalance.

"In 10 years' time, we'll have quite a dramatic change when it comes to the share of people in our society that is 80 years and older, who are also very often care intensive," said Karlsson.

Business leaders in Sweden will lobby hard for exceptions to the even higher threshold likely to come into force next year. But Karlsson said he expected it would take some time before the major parties to became more favourable to labour migration again.

"They associate problems with large-scale migration, so they want to downsize migration in every way, and they don't differentiate between refugee migration and labour migration, unfortunately."

Politics in Sweden is a weekly column looking at the big talking points and issues in Swedish politics. Members of The Local Sweden can sign up to receive an email alert when the column is published. Just click on this “newsletters" option or visit the menu bar.

Comments

See Also

Germany is about to get "the most modern immigration law in the world", the country's interior minister, Nancy Faeser, boasted in June as her government introduced a bill to make it much easier for skilled workers to enter the country.

“This is a wish that has been expressed by large parts of the Danish business community in recent years,” explained Denmark's economy minister, Troels Lund Poulsen, as his government tabled its own bill to cut the minimum wage required for a key work permit scheme.

With a shortage of skilled labour hitting businesses across Europe, these countries' governments are taking action to make it easier for companies to hire from outside the European Union.

But Sweden is going in the opposite direction.

In three weeks' time, the minimum salary to be eligible for a work permit in Sweden will more than double, going from 13,000 kronor a month to at least 80 percent of the median salary, or 27,360 kronor a month (or more for jobs where the industry standard is higher than that). In January, an inquiry is expected to propose how to raise it all the way to the median salary, currently 34,200 kronor.

Sweden's export-driven economy is competing for much the same engineering and IT expertise as Germany's and Denmark's, and its businesses are similarly affected by shortages of skilled labour.

So why the difference?

The main reason is political, argues Tove Hovemyr, social policy expert at the liberal thinktank Fores.

"We have now a government that is supported by and very much dependent on the [far-right] Sweden Democrats' support, and they have to make nice with the party itself, but also try to steal their voters," she explained. "Right now everyone is terrified of looking somewhat pro-migration, and that's why the debates in Sweden and in Denmark and Germany are so vastly different."

The only parties still advocating a liberal labour migration in Sweden, she said, were the Centre Party and the Green Party.

Germany's new government, like Sweden's, promised a "paradigm shift on migration" in the deal between the coalition parties. But while Sweden's agreement promised to bring in the EU's toughest migration law, Germany's promised liberalisation.

In their coalition agreement, the three parties in Germany's new government promised "a new start for migration and integration policy", with would "accelerate and digitise the issue of visas", and which would "enable transnational labour migration" by allowing labour migrants to leave Germany for longer without their residency being at risk.

In Denmark, meanwhile, the decision of the traditional parties of right and left to go into coalition has made the current government the first in 20 years which is under little pressure to tighten immigration rules.

What is unusual in Sweden is that the business lobby, which has traditionally supported the ruling Moderate Party, is opposed to its plans for tighter labour migration.

Hovemyr dismissed Sweden's government's claims that it was making recruitment easier for highly skilled positions by ordering the Migration Agency to reform the work permit process.

"I think that is a way to justify to themselves and to their voters that they're making this policy shift, but no one is happy about it," she said. "Even those who are normally happy with the Moderates and the Liberals governing the country are now very angry about this policy shift."

EXPLAINED:

A recent study by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise estimated that the planned changes to the minimum salary requirement would cut Sweden's GDP by 16 billion kronor and lose the government a total of 5 billion kronor in tax revenues.

"There's a lot of companies that are frustrated now, asking 'how are we going to deal with this?" Patrik Karlsson, a recruitment policy expert at the organisation, told The Local. "They are not happy about it."

He said that Swedish businesses were also facing shortages of labour, and of skilled labour in particular, but said that in Denmark and Germany, politicians were also looking at long-term demographics.

"They see also that from a demographic perspective that they need to strengthen their attractiveness because they in the near future, the demographic analysis indicated that the labour force is going to shrink."

He conceded, though, that Sweden was tightening labour migration policy after 15 years of a system under which employers were able to recruit anyone internationally they wanted so long as they offered pay and benefit levels in line with union collective bargain agreements.

"Our laws on labour migration have been more liberal than in Denmark and Germany, so we were a bit ahead of them in that sense, and now Germany and Denmark have made the same analysis that we did 15 years ago, that we need more foreign talent."

Together with the large number of refugees Sweden received in 2014 and 2015, this period of liberal migration has left Sweden with a better demographic profile, with the labour force expected to increase slightly over the coming decade, after which Sweden again faces an imbalance.

"In 10 years' time, we'll have quite a dramatic change when it comes to the share of people in our society that is 80 years and older, who are also very often care intensive," said Karlsson.

Business leaders in Sweden will lobby hard for exceptions to the even higher threshold likely to come into force next year. But Karlsson said he expected it would take some time before the major parties to became more favourable to labour migration again.

"They associate problems with large-scale migration, so they want to downsize migration in every way, and they don't differentiate between refugee migration and labour migration, unfortunately."

Politics in Sweden is a weekly column looking at the big talking points and issues in Swedish politics. Members of The Local Sweden can sign up to receive an email alert when the column is published. Just click on this “newsletters" option or visit the menu bar.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.